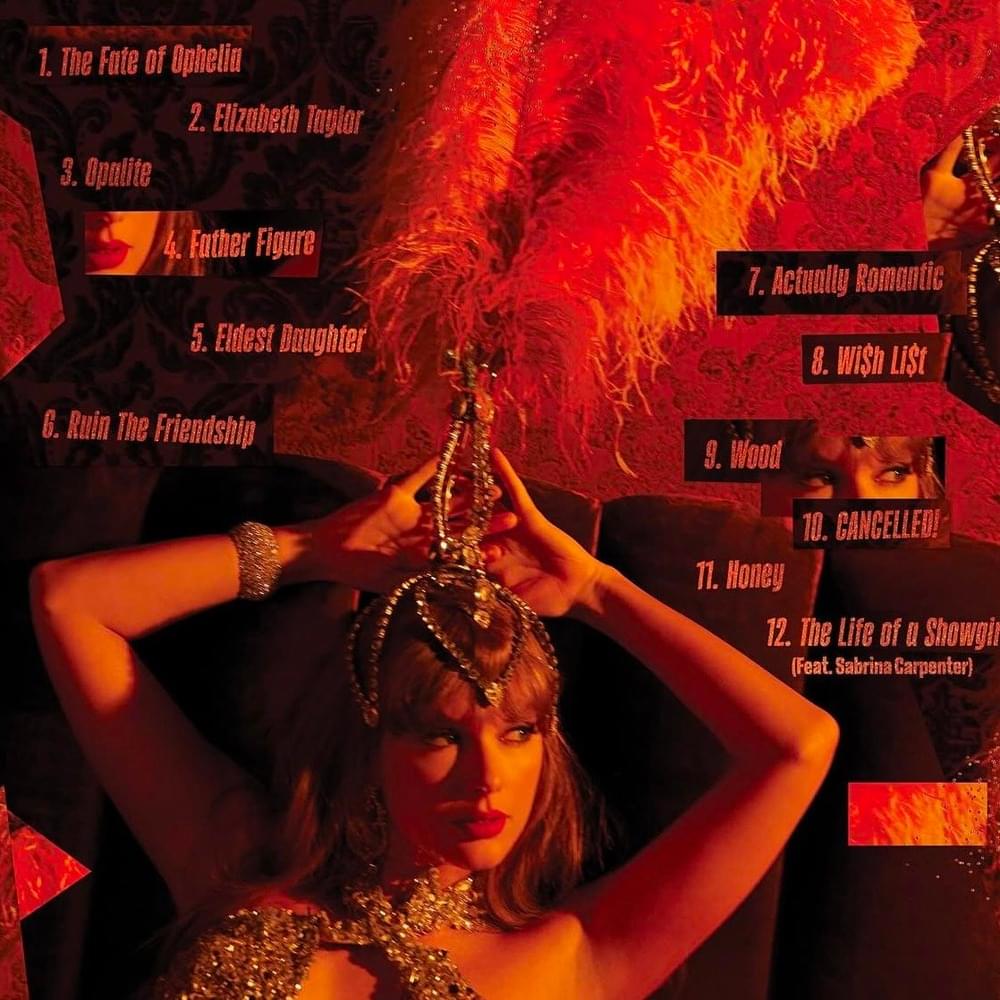

As those who know me well (or, even those who have been around me for any length of time) know, I’m a Swiftie. And I was excited for The Life of a Showgirl like everyone else. I stayed up to listen at midnight and have had it playing in the background since. It’s fun! By no means is it my favorite Taylor Swift album, but there are genuinely enjoyable tracks – “Opalite” is a blast, “Father Figure” tells a dark and compelling story, and the title track gives me the behind-the-scenes showgirl story I was hoping the rest of the album would be.

What I wasn’t prepared for was the discourse. For days straight since the album dropped, I’ve been talking with friends processing their big feelings about it, and I’ve had to actively limit my scrolling across platforms because every other piece of content being pushed my way is some “hot take” about why this album is a disappointment, a betrayal, or proof that Taylor has lost her touch. I hit my limit when I saw multiple people complaining about Taylor’s insistence on making up unrelatable names for songs like “Elizabeth Taylor” and “Ophelia.” Elizabeth Taylor. One of the most famous actresses of the 20th century. Ophelia, from Hamlet. Cultural references are dying by the minute, apparently, and I needed to step back from the internet for my own sanity.

Here’s the thing, though: I happen to be teaching about Taylor Swift in my Religion and Popular Culture class this week, and my students are listening to the Material Girls podcast episode “Taylor Swift x Intimate Publics with Margaret H. Willison.” The timing couldn’t be more perfect – or more illuminating. In that October 2023 episode, recorded as Swift released 1989 (Taylor’s Version) during arguably her biggest cultural moment ever with her in the middle of The Eras Tour, hosts Hannah McGregor and Marcelle Kosman sat down with cultural critic Margaret H. Willison to explore a foundational question: Why is Taylor Swift so successful? Their answer draws on theorist Lauren Berlant’s concept of “intimate publics,” and as I’ve been marinating in the Showgirl discourse all week, I keep coming back to their analysis. I actually think Berlant’s framework helps us understand not just Swift’s success, but why this particular album has generated such intense emotional responses – responses that, when you look closely, aren’t really about the quality of the music at all.

Understanding Intimate Publics

Lauren Berlant developed the concept of “intimate publics” in The Female Complaint: The Unfinished Business of Sentimentality in American Culture (2008) to describe how strangers become emotionally attached through consuming common cultural texts – magazines, novels, films, and yes, pop music. These aren’t just fandoms; they’re spaces where “people feel emotionally attached to people they don’t know and maybe wouldn’t like or couldn’t identify with in any other way.” Intimate publics are constituted by strangers who consume common texts and cultural products, creating a sense of belonging that feels deeply personal even as it’s shared by millions.

Crucially, Berlant argued that for women’s culture specifically, these intimate publics thread together the everyday institutions of intimacy, mass society, and politics through fantasies rather than ideology. They provide what Berlant called “a space of legitimacy that isn’t sanctioned by the dominant public” – a place where women can process shared experiences of disappointment, struggle, and longing that the broader culture often dismissed or minimized.

The Material Girls hosts and Margaret H. Willison applied this framework to Swift because she has somehow managed to take hyper-specific elements of her life – detailed breakups, specific memories, particular emotional moments – and have millions of people relate to them in ways most pop stars can’t. Her diary-esque style of writing serves as a unifying cultural text where women and queer people find community and belonging. Swift’s genius wasn’t just writing good songs; it was creating an intimate public where fans felt she was speaking directly to their interior lives, even as she sang about her own.

The Current Crisis

Fast forward to October 3, 2025, when Taylor released her twelfth studio album, The Life of a Showgirl. YouTuber Ajay’s reaction captures the current mood: “I had high hopes, she set the bar so high. This is a low for Taylor Swift. She needs to take time away. This is not the same person who released Reputation, Folklore, and Red.” A 12-track, 41-minute pop album has sparked passionate discourse across social media, with fans expressing disappointment, confusion, and even a sense of betrayal.

Here’s what’s fascinating: when you examine the specific critiques, they don’t actually hold up as consistent aesthetic judgments. Ajay invokes Reputation and Red as superior works, yet “CANCELLED!” sounds like it could have been a Reputation B-side, and playful tracks like “Wood” or “Ruin the Friendship” mirror Red‘s lighter moments like “Stay Stay Stay” or “Girl at Home” – songs that were never considered lyrical masterpieces but were celebrated as fun.

The “bad lyrics” criticism is even more revealing. Consider the backlash to “Eldest Daughter”:

Everybody’s so punk on the internet / Everyone’s unbothered ’til they’re not / Every joke’s just trolling and memes / Sad as it seems, apathy is hot.

Critics are calling this sloppy writing, complaining that references to memes and internet culture don’t belong in a serious song. Yet these same fans praise folklore‘s “The Lakes” for its brilliant juxtaposition:

I’m not cut out for all these cynical clones / These hunters with cell phones

and

A red rose grew up out of ice frozen ground / With no one around to tweet it

before shifting to

While I bathe in cliffside pools / With my calamitous love and insurmountable grief.

The strategic placement of modern, almost mundane references (“cell phones,” “tweet”) against more poetic imagery is celebrated there – so why not here?

Meanwhile, that same criticized song contains exactly the kind of raw, vulnerable, specific memory work that Swift is famous for:

You know, the last time I laughed this hard was / On the trampoline in somebody’s backyard / I must’ve been about eight or nine / That was the night I fell off and broke my arm / Pretty soon, I learned cautious discretion / When your first crush crushes something kind / When I said I don’t believe in marriage / That was a lie.

This is quintessential Swift – deeply personal, nostalgic, emotionally complex, revealing something previously hidden.

Violating the Terms of Belonging

So if the sonic palette, lyrical techniques, and emotional vulnerability are consistent with her acclaimed work, what’s actually driving the backlash? I’d argue we’re witnessing a rupture in the intimate public itself – and that rupture reveals the unspoken terms of belonging that have governed Swift’s relationship with her fans.

Swift’s previous work invited fans into private pain, complex emotions, and relatable struggles. Whether it was heartbreak, industry betrayal, anxiety, or the messy process of growing up, her music created space for collective processing of difficult feelings. The intimate public she built wasn’t just about loving Taylor Swift; it was about finding your own story reflected in hers, about feeling less alone in your struggles because millions of others were singing along to the same diary entries.

The Life of a Showgirl offers something fundamentally different: straightforward happiness about being in love. Lines like “Have a couple kids, got the whole block looking like you” from “Wi$h Li$t” or “Good thing I like my friends cancelled / I like ’em cloaked in Gucci and in scandal” from “CANCELLED!” don’t invite the same communal processing of shared experience. This isn’t music for processing pain or feeling seen in your struggles; it’s music celebrating contentment with a famous football player, being a billionaire, and dreaming about a traditional family life.

The disconnect becomes even starker with lyrics like:

That view of Portofino was on my mind when you called me at the Plaza Athénée / Ooh-ooh, oftentimes it doesn’t feel so glamorous to be me (from “Elizabeth Taylor”).

As several influencers have noted, “her world has just gotten so much smaller” – but perhaps more accurately, the gulf between her world and her fans’ worlds has become harder to bridge. The billionaire reality is harder to obscure when she’s singing about luxury hotels and Italian coastal views rather than the universal experience of heartbreak or growing up.

This is where Berlant’s framework becomes particularly illuminating. Intimate publics for women’s culture, Berlant argued, often center on a discourse of disappointment, processing the gap between the promises made to women (love, happiness, fulfillment) and the more complicated realities they actually experience. Swift’s earlier work fit perfectly into this tradition. Even her songs about happiness contained complexity, doubt, or vulnerability that kept them within the intimate public’s shared emotional landscape.

But Showgirl largely abandons that discourse of disappointment. Swift sounds genuinely, straightforwardly happy in ways that don’t leave much room for the communal processing that built her intimate public. And perhaps most tellingly, her happiness is attached to deeply conventional markers of success – romantic partnership with a high-status man, dreams of marriage and children, and a traditional domestic fantasy. This isn’t the messy, relatable, slightly broken Swift who made you feel seen; this is Swift living out a fantasy that may not map onto your life in the same accessible way.

The Friend Who Changed

The discourse from within the fandom feels less like music criticism and more like grief – specifically, the kind of grief you experience when a close friend changes drastically and you find yourself saying, “I don’t even know who you are anymore!” This reaction makes perfect sense through Berlant’s framework. Swift was never actually anyone’s close friend, but she was the architect of an intimate public that thrived on her appearing to share our struggles, process our disappointments, and validate our interior lives while we danced alone in our bedrooms.

When the diary fundamentally changes tone – when the struggle transforms into settled contentment, when the vulnerability becomes about being too famous rather than too heartbroken – the terms of belonging shift. Fans aren’t just critiquing an album; they’re mourning the loss of a space where they felt seen and understood. The intimate public that formed around Swift’s music was built on a specific kind of reciprocity: she would continue to articulate complex emotional experiences, and in return, fans would show up, stream, defend, and participate in the world she created.

The Life of a Showgirl disrupts that contract, not necessarily through lower quality songwriting (though, we can definitely have that conversation!), but through a fundamental shift in what Swift is offering and what emotional work her music performs. It’s telling that many fans have noted they don’t hate the album, but that they’re just confused by it, disappointed, unsure where they fit in this new iteration of Swift’s public persona.

Of course, there are plenty of legitimate critiques beyond the framework of intimate publics. Questions about relatability when you’re a billionaire singing about luxury European hotels and how your life “doesn’t feel so glamorous” are valid. Concerns about the increasingly narrow, conventional nature of her dreams – settling down with the right man, having kids who look like him – raise questions about what fantasies we’re being sold and who they serve. The album exists in a complex cultural moment where Swift’s success has made her almost impossible to criticize without being labeled a hater, even as that same success makes her increasingly disconnected from the experiences that originally built her fan base.

But understanding the emotional intensity of the response – the sense of betrayal, the feelings of loss – requires grappling with how intimate publics work and what happens when the person at their center changes the terms of engagement. Swift built something powerful by making millions of people feel intimately connected to her interior life. The current discourse suggests that connection was more conditional than it appeared, dependent on Swift continuing to play a specific role in fans’ emotional lives and continuing to offer vulnerability that feels accessible, struggles that feel shared, and fantasies that feel achievable or at least relatable.

What we’re witnessing isn’t the end of Taylor Swift’s career or even necessarily the dissolution of her fan base. It’s the growing pains of an intimate public confronting the reality that its architect has moved into a different emotional and material space. Swift has successfully straddled being both your best friend who writes poems in her diary and a billionaire megastar – but The Life of a Showgirl suggests that balancing act is becoming harder to maintain. The diary has changed, and with it, so has the nature of the intimacy on offer.

That said, I’m currently dancing to “Opalite” in my living room, and I stand by my recommendation of “Father Figure” as genuinely intriguing character work. Sometimes a fun pop album is just that. But the fact that a fun pop album can generate this much emotional turmoil? That’s the power and the complexity of intimate publics. Dismissing this discourse around Taylor Swift as frivolous pop culture drama would be a mistake – it would repeat the same old pattern of treating women’s and queer people’s cultural spaces as trivial and unworthy of serious analysis precisely because they’re associated with feminized forms of emotion and community. The intensity of feeling around this album reveals something real about how we build belonging, what we expect from our cultural texts, and what happens when the fantasies that unite us no longer hold.

Leave a comment